1. Introduction

Sharpsnout sea bream, Diplodus puntazzo (Sparidae), is an increasingly cultured species in the Mediterranean area due to its high growth rate and food conversion efficiency [1,2]. Amongst the pathologies responsible for the high mortality rates observed in on-growing facilities, enteromyxosis due to Enteromyxum leei (formerly Myxidium leei) [3] accounts for important epizootic episodes [4–8].

This parasite causes severe catarrhal enteritis, which usually causes the death of the fish under extreme cachectic conditions. It has been described in numerous fish species both in aquaria [9] and maricultures [10,11], and experimental transmission to different freshwater and marine fish has been successfully achieved [12–15]. However, clear differences in the susceptibility to infection have been found between different hosts, which could be related to the onset and progress of their immune response. Some information on the innate immune response is available for Sparus aurata [16,17], but it is scarce for D. puntazzo [15,18].

In the present work, the course of the infection, the haematological changes and the histopathological damage were evaluated in on-growing sharpsnout sea bream exposed to E. leei by cohabitation with infected donor fish. Special emphasis was made on the cellular response evaluated in blood (including the respiratory burst), haematopoietic organs and intestine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Donor and recipient fish

Gilthead sea bream (S. aurata) infected by E. leei and routinely kept in the Instituto de Acuicultura Torre de la Sal (IATS) facilities were used as donors (D) (fish weight= 60–250 g). Enteromyxosis was confirmed 28 days before the experiment using a non-lethal PCR assay [see 19] and the prevalence reached 78.3%. Recipient (R) and control (CTRL) juvenile sharpsnout sea bream (D. puntazzo) produced at an Italian hatchery (weight ∼5.0–10 g) were transported alive to the laboratory indoor facilities of the IMIDA-Acuicultura (S. Pedro del Pinatar, Murcia, Spain). Five months later, 90 fish (mean weight= 107.6 g) were transported to IATS facilities. Upon arrival, twenty two fish were sacrificed and checked for the presence of E. leei using PCR, and all of them were negative.

2.2. Experimental design and sampling procedure

R sharpsnout sea bream were exposed to the infection by cohabitation with E. leei-infected gilthead sea bream (D). At day 0, 25 R and 13 D fish were allocated in a 500 L-fibre glass tank. Another tank with 25 R fish served as control. On day 0, 8 CTRL fish were sampled for biometry and serum. Additional samplings (8 R fish) were made at days 10, 20 and 27 postexposure (p.e.), whereas CTRL fish were sampled only at day 10 p.e., due to the accidental loss of the tank after this sampling. Seawater supply (37.5‰ salinity) was from a pump on shore and temperature was maintained between 20.5 and 18 °C using a heating system. All fish were fed daily with a commercial dry pellet diet at about 1% of body weight. Fish were killed by overdose of the anaesthetic MS222 and bled from the caudal vessels before the necropsy. Fish were weighed, measured and the condition factor (CF) calculated with the formula: (weight/length3 )⁎ 100. Part of the blood was used immediately for the measurement of haematological and immunological parameters, and the rest was allowed to clot at 4 °C to obtain serum after centrifugation at 1500 g for 30 min at 4 °C. Serum was stored at −80 °C until further analyses were performed.

2.3. Haematological studies

Freshly obtained blood was drawn into heparinized capillary tubes, centrifuged at 1500 g for 30 min, and the haematocrit was measured. Haemoglobin was determined using a B-haemoglobin photometer (Hemocue AB, Angelhorn, Sweden). The percentages of the different types of leucocytes in circulating blood, as well as the number of total leucocytes and thrombocytes relative to erythrocytes were determined from May-Grünwald Giemsa stained blood smears. Blood cell types were identified according to the available data for other sparids [20–22], in the absence of specific information on D. puntazzo.

2.4. Respiratory burst assay

The respiratory burst activity of blood leucocytes was measured directly from heparinized blood, in terms of luminol-amplified chemiluminescence (CL) emission, following the method of Nikoskelainen et al. [23], after optimisation of reagent concentrations, blood dilutions and reaction kinetics. Briefly, 100 μl of diluted blood (1:25 in Hanks Balanced Salt Solution, HBSS) was dispensed in white flat-bottom 96-well microplates (Costar) and incubated with 100 μl of a freshly prepared luminol suspension (2 mM luminol in 0.2 M borate buffer pH 9.0, with 2 μg ml−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate, PMA) for 1 h at 24–25 °C. CL was measured every 3 min with a plate luminescence reader (Ultraevolution, TECAN) and kinetic curves were generated. Replicate samples were read against a blank in which no blood was added and the integral luminescence in relative light units (RLU) was calculated. Data are presented as the mean ±S.E.M of 10 fish. All the reagents were purchased from Sigma, except HBSS that was from Gibco.

2.5. Histological study

Pieces of the digestive tract (oesophagus, stomach, anterior, middle and posterior parts of the intestine), gall bladder, liver, spleen, kidney and gills were taken for histological processing. Tissue portions were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in Technovit resin (Kulzer, Heraeus, Germany) sectioned, and stained with toluidine blue (TB) and haematoxylin & eosin (H & E). Some sections were also stained with periodic acid-Schiff (PAS). The intensity of infection was evaluated in the histological sections and scored 1 +to 6 + according to the number of parasitic stages per observation field at 120×. Different aspects related to the cellular immune reaction were evaluated in the sections. The haematopoietic activity in kidney and spleen was classified as slight, medium or high, according to the number and activity of haematopoietic cell groups in both organs in 10 microscope fields at 300×. The presence of melanomacrophage centres (MMC) in kidney and spleen, and the presence of rodlet cells and eosinophilic granular cells in the intestine were ranked as scarce or abundant. The leucocyte infiltration in the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria, the detachment of the epithelium from the basal membrane, the presence of residual cells or residual stages within the epithelium, and the existence of epithelial remnants and stages in the lumen were evaluated as absent or present.

2.6. Statistics

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Student–Newman–Keuls method was used to compare the biometrical, haematological and immunological data of the two experimental groups at each sampling point, and also along the time-course of infection. When the tests of normality or equal variance failed, a Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA on Ranks followed by Dunn's method was applied instead. The statistical analyses were performed using Sigma Stat software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the minimum significance level was set at Pb0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Progression of the infection

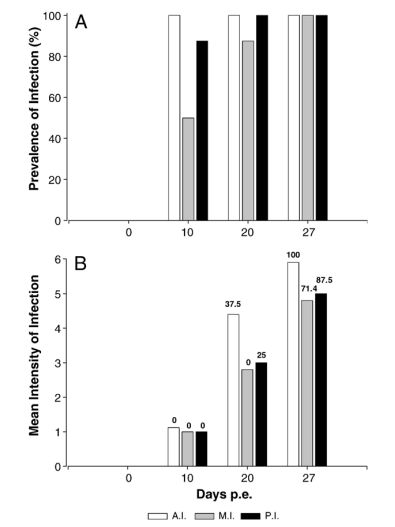

The prevalence of infection was 100% from the second sampling onwards (Fig. 1A), and the mean infection intensity increased progressively from light to severe (Fig. 1B). However, both the prevalence and intensity varied between the different intestinal regions. Infection appeared sooner and progressed faster in the anterior intestine, followed by the posterior intestine, though prevalence values were similar at the last sampling. Accordingly, though the intensity of infection increased progressively during the infection in the three intestinal regions, the rise was faster and reached the highest levels in the anterior intestine (Fig. 1A–B).

Fig. 1. Progression of the infection by Enteromyxum leei in experimentally infected Diplodus puntazzo in the anterior (A.I.), medium (M.I.) and posterior (P.I.) intestinal parts at the different sampling points. A. Prevalence of infection. B. Mean intensity of infection. Numbers above each bar represent the percentage of fish harbouring spores at each sampling time and intestinal section.

The different developmental stages found in R fish were categorized as stages 1 to 5 according to their morphology in histological sections. Stage 1 (ST1) is a trophozoite with one to several nuclei (Fig. 2A–B). In stage 2 (ST2) the primary (P) cell harbours at least one secondary (S) cell and eventually one or more nuclei (Fig. 2C–G). ST1 and ST2 appeared mostly within the intestinal epithelium though few were found in the lamina propria (Fig. 2F), the gill filaments (Fig. 2G), the spleen (Fig. 2H) or engulfed by intestinal macrophages (Fig. 2I).

Fig. 2. Developmental stages of Enteromyxum leei in experimentally infected Diplodus puntazzo. A, B. Stage 1 (ST1) at the base of intestinal epithelium. C–G. Stage 2 (ST2) in the intestinal epithelium (C–E) and lamina propria (F, arrowhead). The generation of a tertiary cell (⁎) is initiating in D. G. ST2 (arrowhead) within a gill filament. H. ST1 in the spleen. I. Residual ST2 engulfed by a macrophage at the base of intestinal epithelium. P: primary cell. S: secondary cell. Toluidine blue-stained sections. Scale bars: 10 μm.

Stage 3 (ST3) consists of a P cell harbouring one or more S cells, which in turn also harbour tertiary (T) cells (Fig. 3A–D). In these ST3 stages, PAS staining was stronger in P than in S cells (Fig. 3D). Stages 4 (ST4) and 5 (ST5) correspond to sporogenesis. ST4 (Fig. 3E–I) comprises a P cell harbouring two sporoblasts in different steps of differentiation and two or more accompanying cells (S cells usually containing darkstained T cells). PAS staining marks very strongly the S cell membranes and the polar capsules (Fig. 3H). Released accompanying cells were occasionally found between the gill lamellae (Fig. 3J). Stage 5 (Fig. 3K–M) refers to fully mature spores, sometimes still contained within the initial P cell, and were often seen released to the intestinal lumen (Fig. 3K, M).

Fig. 3. Developmental stages of Enteromyxum leei in experimentally infected Diplodus puntazzo. A–H. Stages 3 (ST3) and 4 (ST4) within the intestinal epithelium. A–D. ST3 in different steps of development. Notice the more intense PAS-positive staining of P cell in D. E–I. ST4 in progressive steps of sporogenesis with developing spores and accompanying cells (⁎). Note five accompanying cells (⁎) in E, and some enterocyte remnants (arrows) enveloping a luminal ST4 in I. J. Released accompanying cell between the gill lamellae. K–M. Stage 5 (ST5) released to the intestinal lumen (K, M) or within the intestinal epithelium (L). Notice the fully developed spores (K–M) and the accompanying cell (⁎) still within the P cell containing two spores (arrows) (M). P: primary cell. S: secondary cell. T: tertiary cell. Sections are toluidine blue (A, B, E–G, I–M), H & E (C) and PAS (D, H) stained. Scale bars: 10 μm

The presence and relative abundance of the different parasitic stages varied with the progress of the infection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Percentage of R fish harboring the different developmental stages (ST1 to ST 5) of E. leei at the different sampling points.

At day 10 p.e., ST1 and ST2 were dominant, as only one fish presented scarce ST3. From day 20 p.e. and onwards, ll parasite stages were detected, and most fish harboured ST2, ST3 and ST4. At the last sampling, all fish were parasitized by ST2, ST3, ST4 and ST5, but only 12.5% harboured ST1, and sporogonic stages (ST4 and ST5) were clearly more abundant than proliferative stages (ST2, ST3). Some differences were also observed between the intestinal regions. Fully mature spores (ST5) were detected from day 20 p.e. but only in the anterior and posterior intestinal regions (mainly in the anterior). At the last sampling (27 days p.e.), 100% of the fish harboured spores in the anterior intestine, though most of them also contained spores in the medium and posterior intestines as well (Fig. 1B).

E. leei stages were detected in the intestine but not in other parts of the digestive tract, the gall bladder or in blood smears. However, scarce parasitic stages were found in the spleen of one fish at 27 days p.e. (Fig. 2H), and between or within the gill filaments of two additional fish at day 20 p.e. (Figs. 2G, 3J). No CTRL fish was found to be infected by E. leei.

3.2. Biometrical values

The weight of recipient (R) fish varied slightly until day 20 p.e., but decreased significantly at the last sampling (27 days p.e.). Accordingly, the condition factor (CF) for these animals was also significantly lower at 27 days p.e. than in the two previous samplings.

3.3. Haematological studies

R fish exhibited significantly lower haemoglobin (Fig. 5A) and haematocrit content (Fig. 5B) at 27 days p.e. than CTRL fish at 0 and 10 days p.e. Total leucocyte counts (relative to erythrocytes) increased progressively in R fish along the experiment, and values were significantly higher at days 20 and 27 p.e. with respect to CTRL fish at days 0 and 10 (Fig. 1C). No changes were observed in thrombocyte counts. The percentages of some types of leucocytes varied during the infection. The percentage of lymphocytes increased along the infection period, and the difference was statistically significant at day 27 p.e. with respect to CTRL fish at days 0 and 10 p.e. (Fig. 5D). In contrast, a significant decrease in neutrophil percentages was detected in R fish at all sampling points with respect to CTRL fish (Fig. 5E). Eosinophil percentages varied slightly (but non significantly) and only at the last sampling was the mean percentage lower in R fish than in CTRL fish (Fig. 5F). Plasma cells were always scarce but slightly more frequent in R fish than in CTRL fish. Very few monocyte/macrophages were detected in R fish at day 20 p.e. The respiratory burst of circulating leucocytes, measured by chemiluminescence, was significantly enhanced in R fish at 20 day p.e, but the values recovered to the initial levels in the subsequent sampling (Fig. 6).

3.4. Histopathology

A patchy distribution of the parasite in the sections was observed, especially at 20 days p.e. As the infection progressed, the parasite invaded the whole tract and patchiness disappeared. The histopathological study revealed some differences in the status of haematopoietic organs of R fish with respect to CTRL ones (Table 1). The percentage of fish with medium or high haematopoietic activity in kidney and spleen was higher in R fish than in CTRL fish. Melanomacrophage centres (MMC) were more abundant in R than in CTRL fish, mainly at 20 days p.e. In addition, remnants of immune or parasitic cells (frequently engulfed in macrophages (Fig. 7A) were abundant in the kidney of R fish at 20 and 27 days p.e. The severity of the histopathological damage in the intestine of R fish was correlated with the progression of infection and with its intensity (Fig. 7B–H). Scarce or no damage was detected at day 10 p.e., though the presence of residues or residual stages in a high percentage of R fish (87.5%) was remarkable (Table 1). In mild infections, vacuolation started to appear at the base of epithelium (Fig. 7B–C), initiating its detachment. In more advanced infections, parasitic stages occupied extensive areas of the epithelium (Fig. 7D), which could appear partially vacuolated or even necrotic (Fig. 7E), with partly dislodged enterocytes displaying hyperthrophied nuclei (Fig. 7F), and finally detaching from the subepithelial tissue. Consequently, host cell remnants appeared in the intestinal lumen, together with parasitic stages (Fig. 7E). The percentage of fish showing both epithelial detachment and releasing of cell remnants to the lumen increased at the last sampling (Table 1). The subepithelial connective tissue was severely affected in heavy infections, appearing loose, with few cells and filled with remnants of material apparently released from leucocytes (Fig. 7G, H). Eosinophilic granular cells were often observed closely apposed to parasite stages (Fig. 7I–J), sometimes degranulating, whereas rodlet cells were scarce but also close to parasitic cells (Fig. 7K). The histopathological observations in intestinal immune cells deserve special attention. Two types of eosinophilic granular cells (EGCs) were found. The first one (EGC1) harboured abundant large granules that stained fuchsia with H & E (Figs. 7I, 8A–D) and green with PAS, but they were not stained with TB (Fig. 8J). In addition, some of them had scattered PAS-positive granules or their cytoplasm was slightly PAS positive (Fig. 8F). EGC1 were abundant in the epithelium and lamina propria of most CTRL (Fig. 8A–B) and R (Fig. 8C–D) fish at day 10 p.e., but a progressive decrease was observed in the successive samplings of R fish, especially in the epithelium (Table 1). A different type of EGC (EGC2) was identified. It was characterised by smaller granules that scarcely or did not stain with H & E (Fig. 8D, G, H), or with TB (Fig. 8J), and showing some PAS-positive granules, usually with a polarised pattern (Fig. 8I). EGC2 were also present in CTRL fish, but they were more abundant in R fish with mild or severe infection (Fig. 8G–I), in coincidence with the decrease of EGC1 (Fig. 8H–I) and the discharge of PAS-positive granules in the lamina propria (Fig. 7H). Eosinophils (mainly EGC1) were frequently found in close contact with parasitic stages, and discharge of their content was occasionally observed (Fig. 7I). Generally, few lymphocytes were observed, but they were more frequent in R fish, with a maximum at day 20 p.e. (Fig. 8K) and a further decrease at 27 days p.e. (Fig. 8H) (Table 1). Some macrophages appeared in R fish, mainly at the base of the epithelium, and they frequently harboured parasite remnants (Fig. 2I). The scarcity of rodlet cells in the intestinal epithelium was remarkable, and they appeared only in R fish in the two last samplings, particularly at the final one (Fig. 7K; Table 1). Rodlet cells were relatively more abundant in the medium and posterior intestinal regions. No histopathological effect was appreciated in the liver.

4. Discussion

E. leei was successfully and quickly transmitted from D fish to recipient R sharpsnout sea bream. All fish were parasitized from day 10 p.e., a shorter time than those previously reported in cohabitation E. leei infections of this fish host, with prevalences of 40–66.6% at day 12 p.e. and 100% at day 19 p.e. [15,18]. Thus, the current results confirmed that the onset and progression of infection is faster in sharpsnout than in gilthead sea bream [12,16,19] and in Takifugu rubripes [24], under similar temperature conditions. Temperature, fish species and stocks are among the involved factors in E. leei infections (reviewed in [19]). In the current experiment, no mortality due to the disease was recorded, probably due to the relatively short duration of the study period. In other experimental infections of D. puntazzo weighting about 50 g, mortality was very low [15,18]. This is in agreement with the situation observed in the field, as high mortalities are usually recorded mainly in juvenile fish [6]. However, the weight of infected fish decreased as expected, as a typical consequence of the emaciative disease. The decrease in haemoglobin and haematocrit also reflected the disease condition of R fish, though this effect was evidenced only at the last sampling. The histopathological study confirmed the deleterious effect of the parasite. In severe infections, parasites invaded the intestinal epithelium, producing vacuolation and even necrosis and detaching of epithelial cells. These histopathological lesions are similar to those described by Golomazou et al. [15] in the same host and by Tun et al. [25] in Takifugu rubripes, but more severe than what is usual in gilthead sea bream (authors' unpublished observations). In sharpsnout sea bream, some lesions were reported in the liver of heavily infected fish after long-term infections [4,5], in contrast with the absence of hepatic damage in our short term study. In the current experiment, the increasing severity of damage was correlated with the progression of the infection, and also with the development of the parasite that includes proliferative (ST1–ST3) and sporogonic (ST4, ST5) phases similar to those described for E. scophthalmi in turbot [26]. Interestingly, intestine was more damaged when sporogonic stages (ST4 and ST5) were present, although the proliferative ST3 was also abundant. The presence and significance of accompanying cells in sporogonic stages was confirmed, as cells with the same morphology were recognised within the epithelium, apparently initiating new proliferative cycles, as previously suggested by Tarer et al. [27]. No clear indication on the infection route was obtained. Parasite stages could not be detected in blood smears, in contrast to E. scophthalmi infections [26], but the presence of initial stages in the spleen and gills suggests the spreading of the parasite by the blood system, as it has been suggested for E. scophthalmi [26]. This is in accordance with a probable invasion of the intestine mainly through the base of epithelium, as no stages could be detected attached or penetrating through the epithelial border. In addition, the brush border remained quite unaltered even in very intense infections. This situation clearly differed from that observed for E. scophthalmi in turbot, as invasion through the intestinal brush border was considered one of the main routes of infection, and the epithelium was considerably altered [26,28]. In the current work, parasite stages were never found in other parts of the digestive tract apart from the intestine. Contrarily, the parasite was reported in the gall bladder of sharpsnout sea bream suffering E. leei epizootics [4,5] or experimentally infected [15], though mature spores were the only stages found in this location. Haematological, immunological and histopathological changes indicate an effect of the parasitosis on the immune system. Some functions were initially stimulated, as demonstrated by the increase in leucocyte numbers and in the respiratory burst, and the higher percentage of fish showing increased haematopoietic activity and MMC numbers. Thus, in the first steps of the infection, D. puntazzo counteracts it through the activation of some immune factors. However, all fish became highly infected at the end of the experimental period, when a decrease of some immune factors occurred, such as the percentage of circulating neutrophils and the lymphocyte and EGC1 infiltration. A progressive depletion of haematopoietic activity was also described in E. scophthalmi-infected turbot [29]. Available information on the effect of E. leei infection on respiratory burst deals only with head kidney leucocytes of exposed gilthead sea bream, which showed a decrease at day 22 p.e. [17]. No previous information is available on sharpsnout sea bream leucocyte types, either in blood or in intestine. The characterisation of sharpsnout leucocytes is beyond the scope of this work. However, some relevant data in relation to enteromyxosis deserve a special comment. The terminology and nature of fish eosinophilic cells have been controversial and still remain confusing. The term eosinophilic granule cells (EGCs) was introduced by Roberts et al. [30] and is currently used to designate mononuclear eosinophilic granule-containing cells distributed in the connective tissues of various teleosts. EGCs are common in the intestine of salmonids and other fish. Their heterogeneity and their marked staining diversity has been stressed [31,32]. EGCs have been suggested to be mast cells analogous or equivalent [33–36] or similar to mammalian intestinal Panneth cells [37]. Other authors [38] consider that EGCs of bony fish possibly do not have a specific mammalian analogue but rather represent a cell type originating from the evolutionary precursors of both Panneth cells and mast cells. In the current work, besides the abundant circulating eosinophils similar to those previously described in gilthead sea bream [20], we found two apparently different types of EGCs in the intestinal epithelium and lamina propria. However, we cannot fully disregard the possibility of these two types actually being different functional stages of the same cell type, whose staining patterns change with the metabolic status. Scarce information on sparid intestinal EGCs is available for comparison. The cell designated EGC1 in the present work is very similar to the intestinal EGCs of salmonids and other fish. Such cells are described to increase in certain infections and can degranulate after certain stimuli [38–40], as we have observed in the studied enteromyxosis. However, in the current work EGC1 numbers decreased with the progression of the infection, and the level at the last sampling was clearly lower than before the infection, in parallel with an increase in the EGC2-type cells. The recruitment of lymphocytes to the intestinal mucosa occurred from the beginning of the infection, when appreciable changes still had not yet occurred in blood lymphocytes. Interestingly, the rise of circulating lymphocytes at the last sampling coincides with the decrease in the percentage of fish showing lymphocytic infiltration in both epithelium and lamina propria. The scarcity of rodlet cells in our experimental D. puntazzo deserves to be mentioned, as few of them were observed and only in R fish. By contrast, this cell type is very abundant in the intestine of other teleosts, such as S. aurata and Psetta maxima, in which its number increases with intestinal infections such as enteromyxosis (authors' unpublished observations). Such controversial cell type is now accepted to be involved in the fish response to different pathogens [41,42]. The significance of their scarcity with respect to the immune response of D. puntazzo to E. leei remains to be elucidated. Thus, several differences in the host response to Enteromyxum spp. occur depending on the species and the host. Muñoz et al. [18] considered that the immune response to E. leei seems to be lower in sharpsnout than in gilthead sea bream, which could explain the higher severity of the infection in the former species. The involved mechanisms also seem to be different. Cytotoxic activity, the main factor in S. aurata [17], changed very little in exposed D. puntazzo, whereas peroxidase levels increased [18]. The levels of serum lysozyme also deserve to be mentioned. Lysozyme was not detected in D. puntazzo exposed to E. leei by Golomazou et al. [15]. Accordingly, in our experiment, the activity was null in most fish (data not shown). In the scarce lysozyme-positive fish, values were extremely low (roughly 10 times lower than those of gilthead sea bream and 100 times lower than those of turbot). Lysozyme was significantly depleted after chronic exposure of S. aurata to E. leei (authors' unpublished observations). This absence of detectable lysozyme levels in D. puntazzo could also contribute to explain the higher virulence of the disease in this host. This study demonstrates the cellular response of D. puntazzo to E. leei infection. The ineffectiveness of this response, or its depletion at a certain point of infection could contribute to the high virulence of the parasite in this fish host. Further studies to elucidate the specific role of intestinal leucocytes are necessary to better understand the immune response to enteromyxosis.