Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are of interest to immunologists because of their front-line role in the initiation of innate immunity against invading pathogens1 . The signalling pathways activated by different TLRs have therefore been the focus of much research. TLR signalling involves a family of five adaptor proteins, which couple to downstream protein kinases that ultimately lead to the activation of transcription factors such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and members of the interferon (IFN)-regulatory factor (IRF) family.

The key signalling domain, which is unique to the TLR system, is the Toll/interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor (TIR) domain, which is located in the cytosolic face of each TLR, and also in the adaptors2 . Similar to the TLRs, the adaptors are conserved across many species, a striking recent example being in the sea urchin, which is predicted to contain a remarkable 222 TLRs and 26 adaptors3,4.

FIG. 1 illustrates the TIR domain and other domains found in each of the human TIR-domain-containing adaptors. These adaptors are MyD88, MyD88-adaptor-like (MAL, also known as TIRAP), TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ (TRIF; also known as TICAM1), TRIF-related adaptor molecule (TRAM; also known as TICAM2) and sterile α- and armadillo-motifcontaining protein (SARM).

Figure 1 | Schematic representation of protein domains and motifs found in the human TIR-domain-containing adaptor family. MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary-response gene 88) has a Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain, an intermediary domain (ID) and a death domain (DD). MAL (MyD88-adaptor-like protein) contains a phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2 )-binding motif (PIP2) at amino acids 15–35 (REF. 58); tyrosines (Y) at positions 86 and 187 that are phosphorylated by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase66; an aspartic acid (D) at position 198, which is in a caspase-1 cleavage site 72; a serine residue (S) at position 180 in wild-type MAL, or a leucine residue in a MAL variant that confers protection against several infectious diseases73; and a putative tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor (TRAF6)-binding motif (T6BM) at amino acids 188–193 (REF. 63). TRIF (TIR-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing IFNβ) has a receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic interaction motif (RHIM)87 and a T6BM84. TRAM (TRIF-related adaptor molecule) is myristoylated at its amino terminus107 and undergoes phosphorylation by protein kinase Cε (PKCε) at the serine residue at position 16 (REF. 108). SARM (sterile α- and armadillo-motif-containing protein) has two sterile α-motif (SAM) domains110

SARM has now been shown to interact with TRIF and thereby interfere with TRIF function5 . This recent finding, together with other findings in relation to the biochemical regulation of MAL and TRAM, allows us to make conclusions about the role of the five adaptors in TLR signalling and to provide for the first time a detailed molecular description of the earliest phase of TLR signal transduction and therefore the initiation of innate immunity.

How TLR signalling is initiated

TLRs activate a potent immunostimulatory response. The signal that is transmitted from TLRs must therefore be tightly controlled, and there is clear evidence that if TLRs are overactivated, infectious and inflammatory diseases can result6 . What is it therefore that initiates signalling from TLRs and how is this controlled? TLRs occur as dimers7 .

TLR1 and TLR2 heterodimerize, and the resulting dimer senses bacterial triacylated lipopeptides.

TLR2 heterodimerizes with TLR6, which recognizes bacterial diacylated lipopeptides.

TLR4 (the receptor for the Gram-negative bacterial product lipopolysaccharide (LPS)) and TLR9 (the receptor for unmethylated CpG-containing DNA motifs, which occur in bacterial and viral DNA) homodimerize. This is also presumed to be the case for TLR3 (which senses synthetic and viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA)) and TLR5 (which detects flagellin from bacteria).

Most recently, TLR8 (which, similar to TLR7, can sense viral single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) and synthetic imidazoquinolene compounds such as imiquimod) has been shown to dimerize with TLR7 and TLR9, and ligands for TLR8 have been shown to antagonize signalling by TLR7 or TLR9. TLR9 has also been shown to interact with and antagonize signalling through TLR7. These interactions, therefore, indicate that there is added complexity in the TLR7–TLR9 subset of TLRs8 .

Imidazoquinoline is a tricyclic organic molecule; its derivatives and compounds are often used for antiviral and antiallergic creams.

The TLR dimers are thought to be pre-assembled in a low-affinity complex before ligand binding. Once the ligand binds, a conformational change is thought to occur that brings the two TIR domains on the cytosolic face of each receptor into closer proximity, creating a new platform on which to build a signalling complex. The dimerization of the ectodomains of each TLR is likely to be symmetrical, given that the ligand is monomeric.

This has been shown for TLR3 (REF. 9). This symmetrical dimerization will cause the cytosolic TIR domains to associate symmetrically, and consequently force them to undergo a structural reorganization, creating the signalling platform that is necessary for adaptor recruitment. However, crystal structures of the receptor–adaptor interface are still required to define precisely how TLR signalling is initiated. Once signalling is initiated, each adaptor will then ultimately lead to the activation of specific transcription factors, as described in this Review and as summarized in FIG. 2.

Figure 2 | Overview of transcription-factor activation through TIR-domain-containing adaptors for the TLR/ IL-1R superfamily. Each adaptor is differentially used by receptor complexes to positively regulate transcription-factor activation. The exception is SARM (sterile α- and armadillo-motif-containing protein), which inhibits TRIF (Toll/IL-1R (TIR)-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon-β (IFNβ))-mediated transcription-factor activation. These pathways are described in detail in the text. IL-1R, interleukin-1 receptor; IRF, IFN regulatory factor; mDC, myeloid dendritic cell; MAL, MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary-response gene 88) adaptor-like protein; NF-κB, nuclear factor-κB; TLR, Toll-like receptor;TRAM, TRIF-related adaptor molecule .

MyD88

Discovery. MyD88 was first named in 1990 as a protein that was induced during the terminal differentiation of M1D+ myeloid precursors in response to IL-6 — the ‘MyD’ part of the name stands for myeloid differentiation and ‘88’ refers to the gene number in the list of induced genes10. By 1997, the function of MyD88 had been uncovered. MyD88 was first shown to be involved in signalling by the type 1 IL-1 receptor (IL-1R1)11–14 and subsequently in signalling by various TLRs15,16, with the crucial evidence coming from MyD88-deficient mice17,18. These mice were shown to be profoundly unresponsive to ligands for TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, TLR7 and TLR9. Numerous studies have now been carried out on MyD88-deficient mice in the context of disease models.

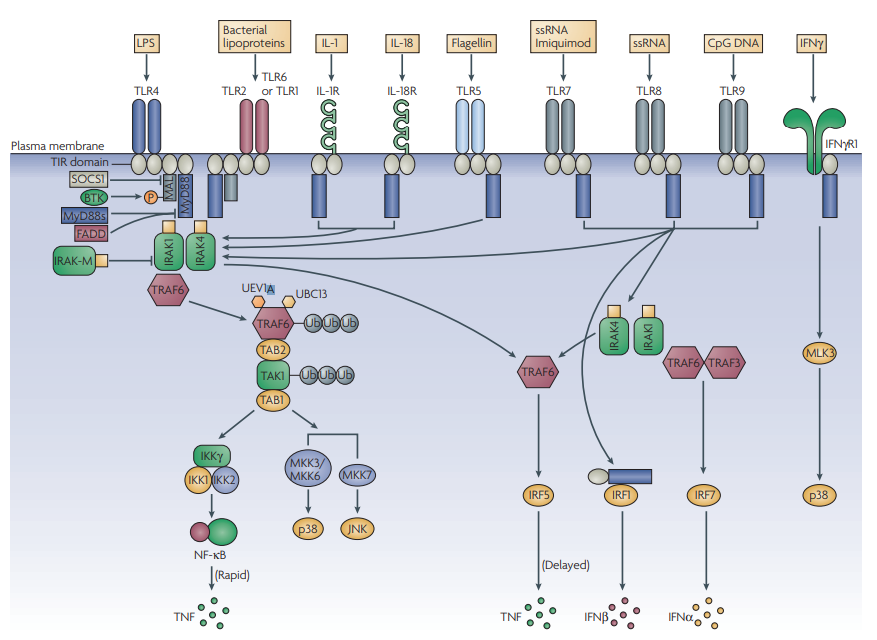

They are resistant to the toxic effect of LPS, and they are also immunocompromised in terms of their ability to fight a range of pathogens, as shown in TABLE 1 (REFS 19–24). MyD88-dependent signalling is involved in transplant rejection25, and it is required for the inflammation that occurs in a model of airway hyperactivity involving the antigen ovalbumin26. However, implicating a lack of TLR signalling in the phenotype of MyD88- deficient mice in models of infectious or inflammatory disease must be done with caution, as these mice are also impaired in their response to IL-1 and IL-18 (REF. 27). Signalling. In terms of signalling, the situation regarding MyD88 has become more complex than previously suspected. FIG. 3 describes the functions of MyD88.

Figure 3 | The world of MyD88. MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary-response gene 88) is the key signalling adaptor for all Toll-like receptors (TLRs; with the exception of TLR3 and certain TLR4 signals), IL-1R and IL-18R. Its main role is the activation of NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB). It is directly recruited to the TIR (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)) domains in certain TLRs (here, shown for TLR5, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9), and acts to recruit IRAK4 (IL-1R-associated kinase 4).

This leads to a pathway involving IRAK1, TRAF6 (tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor 6), TAK1 (transforming-growth-factor-β-activated kinase) and the ubiquitylating factors UEV1A (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1) and UBC13 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 13), which modify and activate TRAF6 and TAK1.

This leads to the activation of the inhibitor of NF-kB kinase (IKK) complex and NF-κB, and the upstream kinases for p38 and JNK (JUN N-terminal kinase).

MyD88 is targeted by negative regulators, such as a shorter form known as MyD88s, which interferes with IRAK4 recruitment, and FADD (FAS-associated via death domain). IRAK-M can also inhibit signalling by preventing the release of IRAK1 and IRAK4 from MyD88. MyD88 also couples to interferon-regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) and IRF1. In the latter case, MyD88 traffics to the nucleus with IRF1.

In the case of TLR2 and TLR4 signalling, a bridging adaptor, MAL (MyD88-adaptor-like protein), is required for MyD88 recruitment. This is subject to regulation by BTK (Bruton’s tyrosine kinase) and SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signalling 1), which promotes MAL degradation. In the case of signalling by TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, the MyD88–IRAK4 pathway also leads through TRAF6 and TRAF3 to the activation of IRF7. Finally, IFNγR1 (interferon-γ receptor 1) can also engage with MyD88, and through mixed-lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) leads to activation of p38. Target genes for each of these pathways are shown. MKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; TAB, TAK1-binding protein; TNF, tumour-necrosis factor; Ub, Ubiquitin.

The activation of NF-κB, JNK (JUN N-terminal kinase) and p38 is absent in MyD88-deficient cells in response to all TLRs tested except TLR4 and TLR3. In both cases, this is because of the alternative use of the adaptor TRIF (described later). As shown in FIG. 3, members of the IL-1R-associated kinase (IRAK) family are recruited immediately downstream of MyD88. IRAK4 seems to be the MyD88-proximal kinase, which in turn recruits IRAK1.

A splice variant of MyD88, known as MyD88s, has been described that prevents the recruitment of IRAK4 to full-length MyD88, and thereby inhibits NF-κB activation28. MyD88s lacks an important ‘interdomain’, which is the region in MyD88 that is involved in IRAK4 interaction. MyD88s is therefore an important negative regulator of TLR signalling and is, in fact, induced by LPS as part of a negative-feedback mechanism. Also of interest is the observation that MyD88s does not inhibit JNK activation, indicating that IRAK4 is not required for this signal29. IRAK2 can also be found in the MyD88 complex (although this has only been shown when IRAK2 is overexpressed), and the fourth and final IRAK, IRAK-M, seems to have an inhibitory role that prevents the dissociation of IRAK1 and IRAK4 from MyD88 (REF. 30).

A key downstream target for IRAK1 is thought to be tumour necrosis-factor (TNF)-receptor-associated factor 6 (TRAF6), which through the recruitment of transforming-growth-factor-β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1) and TAK1-binding protein 2 (TAB2), and the ubiquitylating factors ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 (UEV1A) and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 13 (UBC13) ultimately engages with the upstream kinases for p38 and JNK, and with the inhibitor of NF-κB kinase (IKK) complex, leading to NF-κB activation. These aspects are reviewed in detail elsewhere31. More recent observations have provided further information about the role of MyD88 in TLR signalling. It has now been shown that CD14 is required for MyD88-dependent signalling to NF-κB by TLR2–TLR6 ligands and through TLR4 by a subtype of LPS known as ‘smooth’ LPS, but not by ‘rough’ LPS32.

However, CD14 was required for signalling of rough LPS via TLR4 to the adaptor TRIF to regulate IRF3. These results indicate that the engagement of TLR4 with MyD88 and TRIF is complex and must somehow depend on the conformation of TLR4, which in turn depends on the presence of CD14. Furthermore, CD14 must also be required for the TLR2–TLR6 dimer to have the correct conformation to recruit MyD88. Other recent studies have expanded our understanding of the role of MyD88 in signalling during the host defence response. As shown in FIG. 3, MyD88 is required for the induction of type I IFNs by TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9. MyD88 has also been shown to be essential for the activation of IRF7 by these TLRs, which leads to IFNα production33–35, and a complex comprising MyD88, IRAK1, IRAK4, TRAF6 and IRF7 has been detected36, with IRF7 being phosphorylated by IRAK1. This phosphorylation seems to be a key function for IRAK1 in TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9 signalling, as the IRF7 response is totally abolished in IRAK1-deficient cells, whereas NF-κB activation is only partially impaired37. In the case of TLR9, IRF7 activation seems to require a stable interaction between MyD88 and the TIR domain of TLR9, which occurs on the cytosolic side of endosomes35. MyD88 also interacts with IRF5 and IRF1 and is required for the activation of these IRFs. IRF5 was identified as being crucial for the induction of proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs by all TLRs tested38. The association of MyD88 with IRF1 seems to be required for translocation of IRF1 to the nucleus in myeloid DCs39, and IRF1 is required for the induction of several TLR-dependent genes in these cells. IFNγ is required to induce IRF1, and this might be the basis for the priming effect of IFNγ on TLR action. Another intriguing link to the IFNγ system is the reported association between MyD88 and IFNγ receptor 1 (IFNγR1)40. MyD88 recruits mixed-lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) downstream of IFNγR1, which in turn activates p38. An alternative signalling pathway has therefore been revealed for MyD88 that does not involve TIR-domain-containing receptors. Another TLR-independent function of MyD88 was reported in CD95 (also known as FAS) signalling. CD95 signalling enhances IL-1R1 signalling by redirecting FADD (FAS-associated death domain) from a complex with MyD88 to the death domain of CD95, thereby allowing IL-1R1 to signal through MyD88 (REF. 41). Similarly, the TIR-domain-containing receptor ST2, which belongs to the IL-1 receptor subgroup, can sequester MyD88 and interfere with signalling by TLR4 (REF. 42). Both of these studies indicate that MyD88 is an important point of control for signalling through various receptors, and this is further supported by the observation that transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ), an antiinflammatory cytokine that can interfere with TLR4 signalling, promotes the ubiquitylation and degradation of MyD88 (REF. 43). An additional MyD88-interacting signalling component that has been recently identified is TRAF3. In TRAF3-deficient cells, the induction of type I IFNs and IL-10, but not pro-inflammatory cytokines, was impaired in response to TLR3, TLR4 and TLR9 activation44. TRAF3 also interacts with TRIF, and is required for activation of the kinase TBK1 (TRAF-family-memberassociated NF-κB-activator-binding kinase 1)45. TRAF3, therefore, seems to have a key role in both MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signalling. A final aspect concerning signalling by MyD88 relates to the timing of signals from TLR4. In MyD88-deficient cells the time course of activation of NF-κB is delayed in the case of TLR4 signalling. Two studies have provided an explanation for this finding. NF-κB activation occurs in two waves in response to LPS46,47; the first wave is activated by MyD88 directly engaging with the pathway that leads to the IKK complex; however, the second, delayed wave depends on autocrine TNF production, which is initiated by TRIF activation of IRF3. This two-phase mechanism has been modelled and when each phase was examined in isolation, both were shown to exhibit damped oscillatory behaviour46. This combination of two out-of-phase oscillatory-based responses gives rise to stability in the NF-κB activation pathway, which presumably reflects the importance of this pathway for the initiation of host defence by TLR4. Structural requirements for adaptor recruitment to TLRs. The TIR domain is defined by a motif of ~160 amino acids composing five β-sheets surrounded by α-helices and connected together by flexible loops48. Conservation between TIR domains reflects the structural requirement of this folding pattern. However, the surface properties of TIR-domain-containing adaptors have been shown to be distinct and it has been proposed that electrostatic complementarity might explain specific interactions between adaptors and TLRs. This is discussed in more detail in relation to MAL (see below). Two particular loop regions within the TIR domain have been studied; these are known as the ‘BB loop’ and ‘DD loop’. Each TIR domain has both of these loops. The BB loop occurs in the Box 2 sequence of the TIR domain, which in most TIR domains contains a key proline residue. This proline was shown to be mutated to a histidine in the TLR4 of C3H/HeJ mice, which rendered the mice non-responsive to LPS. The BB loop of TLR2 and the DD loop of MyD88 are required for the two proteins to interact48,49, and the DD loop of TLR2 interacts with the BB loop of TLR1 (REF. 50). A simple model might therefore be that TLR dimerization occurs as a result of interaction between the DD loop of one TIR domain and the BB loop of the other TIR domain, and that the adaptor dimer then interacts with the receptor dimer through other regions in the TIR domain that are dependent on electrostatic complementarity, although this has yet to be demonstrated. We can provisionally conclude that the BB and DD loops of TIR domains are required for TIR–TIR interactions. Structural studies on the complex between MyD88 (or indeed any of the adaptors) and a TLR are required to clarify the situation. Peptides based on the BB loop of MyD88 and the other adaptors have been tested as possible inhibitors of signalling but a clear picture of the use of specific adaptors by different TLRs has yet to emerge from these studies51. However a peptidomimetic based on the BB loop of MyD88 has been designed that interferes with the interaction between MyD88 and IL-1R1, and inhibits IL-1 signalling52. Ultimately, the hope is that inhibitors might be designed that would specifically interfere with adaptor recruitment and modify signalling in diseases involving TLRs.

Recently, an interesting observation has been made in relation to a region in MyD88 defined as the Poc site53. Random germline mutagenesis was used to create a pheno variant of TLR signalling known as Pococurante (Poc). Mice with this variant were shown not to respond to any TLR ligands that signal through MyD88, with the notable exception of diacyl lipopeptides (which signal though TLR2–TLR6 dimers). The Poc mutation results in the missense error Ile179Asn in MyD88. Ile179 in MyD88 is therefore a key amino acid in all MyD88-mediated TLR signalling, with the exception of TLR2–TLR6 signalling. The model that was proposed from this study was one in which the role of the Poc site in MyD88 is to interact with the BB loop of the recruiting TLR. Both the Poc site and the BB loop are required for all MyD88–TLR interactions, except in MyD88 interactions with TLR2– TLR6, which only seem to require either the Poc site or the BB loop. Although, why this should be the case is unclear. A final point of interest in this study was that the mice bearing the Poc mutation were not impaired in their ability to contain infection with Streptococcus pyogenes. This contrasts with MyD88-deficient mice, which were highly susceptible to the infection. Given that the only antibacterial TLR that apparently functions in the Poc mutant mice is TLR2 in combination with TLR6, the sensing of diacyl lipopeptides by TLR2–TLR6 through MyD88 must be of primary importance in the host defence response to S. pyogenes, emphasizing the specificity of TLR use during infection.