MAL

The second adaptor in the TIR-domain-containing adaptor family to be discovered was MAL54,55. MAL is required for signalling by TLR2 and TLR4, serving as a bridge to recruit MyD88 (REFS 54–58). A dominantnegative version, in which the Box 2 proline in MAL was mutated to a histidine, resulted in the inhibition of TLR4 signalling, but not IL-1 signalling55. In addition, a peptide based on the BB loop region of MAL was shown to inhibit TLR4 but not TLR9 signalling54. These results were the first indication that there is specificity in TIR-domain-dependent signalling. This specific role for MAL was confirmed in MAL-deficient mice, which were shown to be defective in TLR4 signalling in terms of cytokine induction. IL-1 and TLR9 signalling were normal, but TLR2 signalling was also impaired56,57. This led to the conclusion that MAL is required for signalling only by TLR2 and TLR4 (FIG. 3).

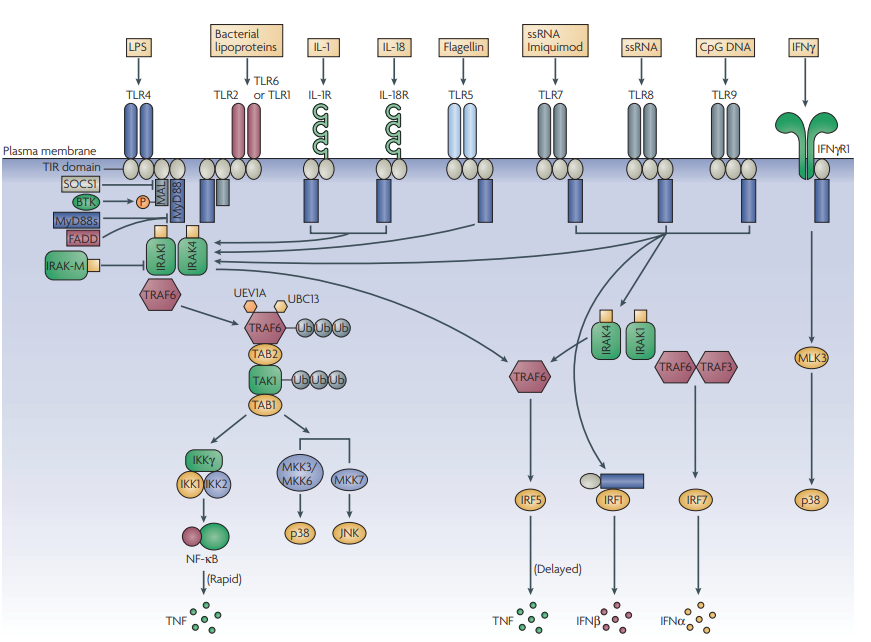

Figure 3 | The world of MyD88. MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary-response gene 88) is the key signalling adaptor for all Toll-like receptors (TLRs; with the exception of TLR3 and certain TLR4 signals), IL-1R and IL-18R. Its main role is the activation of NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB). It is directly recruited to the TIR (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (IL-1R)) domains in certain TLRs (here, shown for TLR5, TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9), and acts to recruit IRAK4 (IL-1R-associated kinase 4). This leads to a pathway involving IRAK1, TRAF6 (tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor 6), TAK1 (transforming-growth-factor-β-activated kinase) and the ubiquitylating factors UEV1A (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1) and UBC13 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 13), which modify and activate TRAF6 and TAK1. This leads to the activation of the inhibitor of NF-kB kinase (IKK) complex and NF-κB, and the upstream kinases for p38 and JNK (JUN N-terminal kinase). MyD88 is targeted by negative regulators, such as a shorter form known as MyD88s, which interferes with IRAK4 recruitment, and FADD (FAS-associated via death domain). IRAK-M can also inhibit signalling by preventing the release of IRAK1 and IRAK4 from MyD88. MyD88 also couples to interferon-regulatory factor 5 (IRF5) and IRF1. In the latter case, MyD88 traffics to the nucleus with IRF1. In the case of TLR2 and TLR4 signalling, a bridging adaptor, MAL (MyD88-adaptor-like protein), is required for MyD88 recruitment. This is subject to regulation by BTK (Bruton’s tyrosine kinase) and SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signalling 1), which promotes MAL degradation. In the case of signalling by TLR7, TLR8 and TLR9, the MyD88–IRAK4 pathway also leads through TRAF6 and TRAF3 to the activation of IRF7. Finally, IFNγR1 (interferon-γ receptor 1) can also engage with MyD88, and through mixed-lineage kinase 3 (MLK3) leads to activation of p38. Target genes for each of these pathways are shown. MKK, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase; TAB, TAK1-binding protein; TNF, tumour-necrosis factor; Ub, Ubiquitin.

TLR2 signalling in MAL-deficient cells was impaired to a greater extent than TLR4 signalling, with no evident activation of NF-κB or p38. For TLR4 signalling, the phenotype in MAL-deficient cells was the same as that for MyD88- deficient cells — involving a delay in NF-κB and p38 activation. Similar to MyD88, MAL was found to have no role in the activation of IRF3 and so the conclusion was drawn that MAL is a component of the MyD88 pathway. This would explain why TLR2 signalling was more impaired than TLR4 signalling, as TRIF, which in TLR4 signalling was shown to induce TNF production to promote the later activation of NF-κB, is not used in TLR2 signalling. MAL-deficient mice have not been tested in as many disease models as have MyD88-deficient mice. However, MAL has been shown to be crucial for early immune responses to Escherichia coli and LPS in the lung59, and also in the induction of antimicrobial peptides in the lung in response to Klebsiella pneumoniae, but not to Pseudomonas aeruginosa60 (TABLE 1). LPSinduced airway hyper-reactivity has been shown to involve MAL61. MAL also has a role in the injury that occurs in the heart in a model of ischemia–reperfusion injury62. A clear role for MAL as a bridging adaptor for MyD88 has been shown. MAL has a binding domain in its N-terminus that binds to phosphatidylinositol-4,5- bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2 )58. This mediates the recruitment of MAL to the plasma membrane (which is the key PtdIns(4,5)P2 containing membrane) and in particular to microdomains that contain TLR4. MyD88 does not bind directly to TLR4, but instead interacts with MAL in association with TLR4. This is consistent with the electrostatic surfaces of the TIR domains of MAL and MyD88. The TIR domain of MAL is largely electro-negative on its surface, whereas that of MyD88 is electro-positive. As the TIR domain in TLR4 is also electro-positive, it would be predicted to repel MyD88 but allow MAL to interact, which is consistent with molecular modelling of the interaction between TLR4 and MAL49. When the PtdIns(4,5)P2 -binding domain in phospholipase C was grafted onto the N-terminus of MyD88, signalling to NF-κB could be reconstituted in MAL-deficient cells, which strongly indicates that the only function of MAL in relation to the NF-κB pathway is to recruit MyD88. Whether other TLR4-mediated MyD88-dependent signals, such as IRF5 activation, are similarly dependent on MAL was not examined. This study also indicates that the amount of PtdIns(4,5)P2 will determine whether MAL is recruited, and that manipulation of PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels will regulate MAL-dependent signalling. New features of MAL have recently been uncovered that distinguish it from MyD88. First, MAL has a TRAF6-binding domain, and MAL might therefore participate in the recruitment of TRAF6 to the signalling complex63. In addition, MAL undergoes tyrosine phosphorylation by Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK), which has a role in both TLR4 and TLR2 signalling64–66, and in turn leads to the increased phosphorylation of the p65 subunit of NF-κB67, which is required for transactivation of gene expression. The phosphorylation of MAL by BTK is required for MAL to signal, but tyrosine-phosphorylated MAL is subject to suppressor of cytokine signalling 1 (SOCS1)-mediated degradation68. These data provide an explanation for why SOCS1-deficient cells are hyper-responsive to LPS69,70, as the pathway to p65 phosphorylation and transactivation through MAL is particularly sensitive to SOCS1. It should be noted, however, that BTK also has a role in signalling by other TLRs, notably TLR8 (REFS 64,71), and so there are likely to be other targets for BTK in TLR signalling. MAL has also recently been shown to interact with caspase-1, with cleavage of MAL by caspase-1 being required for MAL to activate NF-κB72. Finally, a variant of MAL has been found in humans that confers resistance to the infectious diseases malaria, tuberculosis and pneumococcal pneumonia. Wild-type MAL has a serine at position 180, whereas the variant has a leucine at this position. Khor and colleagues have found that being heterozygous for MAL halves the risk of these diseases73. The molecular basis for this involves the impaired recruitment of the leucine form of MAL to TLR2. Heterozygotes are therefore likely to be protected from disease because they have a decreased level of signalling from TLR2 and/or TLR4, which is sufficient for host defence but not for the over-production of inflammatory cytokines that is involved in disease pathogenesis. Hawn and colleagues have also studied the role of this variant in decreased susceptibility to tuberculosis, with three other single-nucleotide polymorphisms also occurring in MAL74.

TRIF

Discovery. MAL was initially thought to control the TLR4-mediated, MyD88-independent pathway leading to IRF3 and delayed NF-κB activation. However, the discovery of the role of MAL as a bridging adaptor in the MyD88-dependent pathway left a gap in our understanding of how TLR4 could mediate type I IFN induction. This gap was filled by TRIF, which is now known to control the TLR4-induced MyD88-independent pathway, and also to be the exclusive adaptor used by TLR3. Similar to MAL, TRIF was identified by database screening for TIR-domain-containing proteins75, but also independently in a yeast two-hybrid screen with TLR3 (REF. 76). In contrast to MAL or MyD88, overexpression of TRIF led to the induction of the IFNB promoter75,76. Furthermore, TRIF-deficient mice were impaired in both TLR3- and TLR4-induced IFNβ production and activation of IRF3, and inflammatory cytokine production was impaired in signalling through TLR4 but not TLR2, TLR7 or TLR9 in macrophages77. Importantly, in cells deficient both in TRIF and MyD88, LPS-induced NF-κB activation was completely abolished, thereby showing that TRIF accounts for the MyD88-independent aspect of TLR4 signalling. Also, in double-deficient macrophages deficient in both TRIF and MyD88, no genes were upregulated in response to LPS78. Examination of single-deficient macrophages showed that the contribution of MyD88 to mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) activation is likely to be more significant than that of TRIF, as genes that are regulated by MyD88 were regulated by messenger RNA stability (presumably through MAPKs), as well as by transcription78. A further study, in which random germline mutagenesis led to a phenovariant known as Lps2, independently confirmed the role of TRIF. In these mice, cytokine responses to polyinosinic–polycytidylic acid (polyI:C) were abolished, and LPS-induced responses were impaired79. The Lps2 mutation mapped to Trif, giving rise to a frameshift. Mice homozygous for Lps2 were resistant to a normally lethal dose of E. coli LPS, and succumbed to cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection more readily (TABLE 1). Macrophages isolated from Lps2 homozygotes were also compromised in their ability to suppress vaccinia virus (VACV) replication. A follow-on study showed that, in the absence of TLR3, mice infected with CMV had increased viral titres in the spleen, slightly increased mortality, decreased serum levels of IFNs and cytokines, and decreased activation of natural killer (NK) cells and NKT cells80. Clearly then, the TLR3–TRIF pathway is important for controlling DNA viruses such as VACV and CMV. So, TRIF was established as the adaptor controlling both TLR3- and TLR4-mediated IFN production, through the activation of IRF3 (REF. 81). As polyI:C-mediated IL-6, TNF and IL-12 induction were impaired in macrophages from IRF5-deficient mice, TRIF, similar to MyD88, probably also mediates IRF5 activation38. TRIF directly engages with TLR3, whereas TRAM bridges the TLR4 interaction (see below). Another important LPS–TLR4- mediated pathway known to be independent of MyD88 is the upregulation of co-stimulatory molecules and MHC class II molecules by dendritic cells (DCs), and TRIF was shown to mediate this pathway through the induction of type I IFNs82. This is important in vivo, as when LPS was used as an adjuvant, TRIF was essential not only for co-stimulatory molecule upregulation, but also for specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses, although the T-cell responses were also dependent on MyD88. In response to polyI:C, both TLR3–TRIF-dependent and -independent pathways were involved in co-stimulatory molecule expression.

Signalling. TRIF uses some shared and some unique signalling molecules compared with MyD88, as shown in FIG. 4.

Figure 4 | Signalling pathways mediated by TRIF and their regulation by SARM. a | TRIF (Toll/interleukin 1 receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon-β) is used by both Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3; shown here) and TLR4 (through TRAM) to mediate NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB) and interferon-regulatory factor (IRF) activation, and to induce apoptosis. Ligand engagement by the TLR complex results in TRIF recruitment through its TIR domain. TRIF has distinct proteininteraction motifs that allow it to (directly or indirectly) recruit the effector proteins TBK1 (tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor-associated factor (TRAF)-family-memberassociated NF-κB-activator-binding kinase 1), TRAF6 and RIP1 (receptor-interacting protein 1). It is still unclear how TRIF uses TRAF3 to induce IRF3 activation, but TBK1 might be recruited to TRIF through TRAF3, and NAP1 (NAK-associated protein 1; not shown). NF-κB is activated by two distinct pathways, mediated by TRAF6 and RIP1 engaging different ends of TRIF. RIP1 also activates a pathway involving FADD (FAS-associated death domain) that facilitates TRIF-induced apoptosis through caspase-8. b | In resting cells, levels of SARM (sterile α- and armadillo-motifcontaining protein) are low. Ligand stimulation of either TLR3 or TLR4 leads to a rapid increase of SARM expression, which correlates with increased association between SARM and TRIF. This inhibits downstream signalling by TRIF, probably by preventing the recruitment of TRIF effector proteins. IKK, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase

As mentioned above, TRAF3 has been recently identified as being crucial for both MyD88 and TRIF signalling to induce type I IFN through IRF3 by different TLRs (REFS 44,45). To mediate IRF3 activation, the N-terminal region of TRIF was proposed to engage with TBK1 (REF. 83), which is now known to be the crucial upstream kinase for IRF3 activation in most pathways, including signalling through TLR3 and TLR4 (REF. 84). However, it is now thought that TRIF associates with TBK1 through NAK-associated protein 1 (NAP1) (REF. 85) and possibly TRAF3. For NF-κB activation, two separate pathways seem to bifurcate from TRIF, and these map to distinct sites at the N- and C-termini of TRIF. Similar to MAL, TRIF has consensus TRAF6-binding motifs (FIG. 1) in the N-terminal region in the case of TRIF; mutating these motifs decreased TRIF-induced NF-κB, but not IRF3, activation83,86. However, the role of TRAF6 in TRIF signalling is still controversial as in macrophages from TRAF6-deficient mice, in contrast to the situation in TRAF6-deficient mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)86, TLR3 signalling was not affected87. However, there is also a distinct route to NF-κB activation involving the C-terminus of TRIF, which contains a receptor-interacting protein (RIP) homotypic inter action motif (RHIM). TRIF was found to recruit both RIP1 and RIP3 through this domain, and in MEFs deficient in RIP1, polyI:C-induced NF-κB activation was completely blocked88. By contrast, RIP3 negatively regulated the TRIF–RIP1–NFκB pathway. Interestingly, the absence of RIP1 had no effect on TLR4 signalling, indicating that TLR3 and TLR4 might use TRIF differentially. However, a different study found that both TLR3- and TLR4-mediated NF-κB (but not IRF3) activation were affected by the absence of RIP1 (REF. 89). Further differences in the MyD88-independent pathway for TLR3 and TLR4 were revealed by Wietek et al.90, who showed that IRF3-mediated activation of IFN-sensitive response elements (ISREs) by TLR4 but not TLR3 required the p65 subunit of NF-κB. In addition to NF-κB and IRF3 activation, TRIF mediates a third distinct signalling pathway for TLR3, that of induction of apoptosis. In fact, on the basis of overexpresion studies, it has been proposed that TRIF is the only one of the five adaptors that can mediate apoptosis91. This pathway also uses the C-terminal RHIM of TRIF, and seems to involve RIP1, FADD and caspase-8 (REFS 92,93). This apoptotic pathway has also been shown to be active for TLR4, to be MyD88 independent, and to be responsible for bacterial-induced apoptosis of infected macrophages94. The TRIF pathway was also shown to control TLR4-mediated bacterial-induced DC apoptosis in vivo94. A further TRIF-specific and MyD88-independent pathway for TLR4 has been recently identified that provides a molecular mechanism to explain how LPS upregulates MHC class II expression during DC maturation. This involves LPS-induced activation of the small G protein RHOB (RAS homologue gene family, member B) through TRIF and the guanine-nucleotide-exchange factor H1 (GEFH1)95.

Negative regulation. Similar to MyD88, endogenous strategies for downregulating TRIF signalling have been identified. However, most of these are not specific for TRIF, and they either target MyD88 and TRAF6 signalling, or affect downstream components of the TRIF pathway, such as TBK1 or IRF3, and thus exert an effect on other signalling systems that converge on these components (for example, the RIG-I pathway (retinoic-acid-inducible gene I pathway)). Examples of molecules that downregulate both the MyD88 and the TRIF pathways include TRAF1 (REF. 96) and A20 (REF. 97), whereas suppressor of IKKε (SIKE)98 and cis–trans peptidylprolyl isomerase, NIMA-interacting 1 (PIN1)99 inhibit IRF3 activation through TRIF-dependent and -independent pathways. Furthermore, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), which exerts multiple effects on both MyD88-dependent and -independent TLR pathways has been shown to interact with TRIF, and inhibition of PI3K activity increased TRIF-mediated NF-κB activation100. The phosphatase SHP2 (SRC homology 2 (SH2)-domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase 2) has recently been shown to inhibit TRIF-dependent, but not MyD88- dependent, cytokine and IFN induction101. SARM, the fifth TIR adaptor, is a specific negative regulator of TRIF in that it does not inhibit the MyD88 pathway or non-TLR responses (see later). As well as endogenous regulators of TRIF function, pathogen-derived molecules have also been shown to regulate TRIF activity. To successfully replicate and spread within a host, every virus must have ways of overcoming or suppressing the antiviral response. Consistent with a role for TRIF in containing viruses through type I IFN induction, at least two viruses have been shown to contain proteins that antagonize TRIF. VACV encodes two proteins, A46 and A52, that differentially affect TRIF signalling in a non-redundant manner, as deletion of either gene in isolation led to an attenuated phenotype in a murine intranasal model of infection102,103. So, targeting TLR signalling pathways in infected cells confers an advantage on VACV in vivo. A strategy to evade detection by the TRIF-dependent pathway has also been identified for hepatitis C virus (HCV). This virus has a serine protease that can cleave TRIF and thus prevent TLR3 signalling to NF-κB and IRF3 (REF. 104). The same protease can also target IPS-1 (REF. 105) (also known as CARDIF, VISA and MAVS; the signalling adaptor for the RIG-I-mediated viral-RNA detection system), and so HCV can disable both the TLR3 and RIG-I detection pathways with a single protein.

TRAM

The fourth adaptor to be identified was TRAM (also known as TICAM2)81,106,107. This adaptor was also discovered using bioinformatics, followed by a combination of overexpression studies, dominant-negative mutant analysis, interaction studies with TRIF and studies in TRAMdeficient cells, which showed that TRAM functions exclusively in the TLR4 pathway. TRAM is therefore the most restricted of the adaptors in terms of TLR action. Although TRAM interacts with TRIF, its role seems to be more general than that of TRIF for TLR4 signalling in that the activation of signals and induction of cytokines by LPS is more impaired in TRAM-deficient cells than in TRIF-deficient cells. The basis for this is not clear, as, if TRAM were only to function as a bridging adaptor for TRIF recruitment, we might expect the phenotypes of the TRAM- and TRIF-deficient mice to be similar for LPS signalling. TRAM is required for the induction of TNF, IL-6, CD86 and a range of IRF3-dependent genes. Similar to TRIF, TRAM is required for the late activation of NF-κB, as well as for IRF3 activation. The discovery of TRAM allowed a detailed description of adaptor use by TLR4, as shown in FIG. 5.

Figure 5 | TIR-domain-containing adaptor usage by TLR4. In terms of adaptor usage, Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) is the most complex of the TLRs; it requires four signalling adaptors to function upon activation by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)– MD2. In an apparently identical manner to TLR2, it uses MAL (MyD88 adaptor-like protein) as a bridging adaptor to recruit MyD88 (myeloid differentiation primary-response gene 88) and to activate the NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB) pathway and p38 and JNK (JUN N-terminal kinase) MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathways. MAL is recruited to plasmamembrane microdomains containing the phospholipid PtdIns(4,5)P2 (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate). These microdomains also contain TLR4. MAL subsequently recruits MyD88, and is a substrate for BTK (Bruton’s tyrosine kinase), which seems to be required for its activation and subsequent degradation. The other pathway activated by TLR4 involves TRAM (TRIF-related adaptor molecule). Similar to MAL, TRAM is also membrane proximal, but the mechanism of activation is different. It requires the attachment of a myristate group to TRAM, which lodges in the plasma membrane. TRAM is also a substrate for PKCε (protein kinase Cε) and must undergo phosphorylation to be active. It recruits TRIF (Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR)-domain-containing adaptor protein inducing interferon-β), which in an identical manner to the TLR3 pathway, activates pathways involving TBK1 (tumour-necrosis-factor-receptor (TNFR)-associated factor (TRAF)-familymember-associated NF-κB (nuclear factor-κB)-activator-binding kinase 1) to IRF3, TRAF6 to NF-κB, and RIP1 to apoptosis. Also similar to TLR3 signalling, SARM antagonizes TRIF in TLR4 signalling (not shown). FADD, FAS-associated death domain; IKK, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase; IRF, interferon-regulatory factor; TRAF, TNFR-associated factor.

Recently two biochemical modifications have been identified that are important for TRAM function108,109. The N-terminus of TRAM undergoes constitutive myristoylation and this is required for TRAM to be membrane associated108. This is therefore analogous to MAL, which binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 in the plasma membrane. TRAM has been shown to act as a bridging adaptor for TRIF107, a situation that is again analogous to the use of MAL as a bridging adaptor for MyD88 (REFS 54,55). Mutation of the myristoylation motif in TRAM abolishes its ability to signal. A second important modification is phosphorylation of TRAM on the serine at position 16 by protein kinase Cε (PKCε)109, which is proximal to the myristoylation site. This is a crucial event in TRAM signalling, as, if phosphorylation is inhibited, TRAM signals are impaired, and a mutant TRAM that cannot undergo this modification is inactive. PKCε is an essential component of the LPS-induced signalling pathway in macrophages110, and TRAM is probably a key target for PKCε. However, the precise functional consequences of PKCε-mediated phosphorylation for TRAM are as yet unknown. A key unresolved question is whether TRAM and MAL are mutually exclusive in TLR4 signalling. It is possible that TLR4 is unable to interact with both adaptors simultaneously. An intriguing possibility is that signalling pathways might be governed by whether TRAM or MAL is recruited, and the fine-tuning of signalling might depend on the covalent modification of each protein.

SARM

SARM, the last of the five adaptors to be assigned a role in TLR signalling, is in fact the most evolutionarily ancient, being the only member of the family to have a clear orthologue in Caenorhabditis elegans. SARM was initially identified in 2001 as a human gene encoding an orthologue of a Drosophila melanogaster protein with two sterile α-motifs (SAMs) and HEAT/armadillo repeats111. SARM was also reported to be conserved in mice and C. elegans. Initially, the presence of a TIR domain in SARM was not reported, and the existence of SAM motifs did not provide many clues on the function of the protein, as these protein–protein interaction motifs have a large degree of functional diversity112. The realization that SARM had a TIR domain, and that in C. elegans only two genes encoded TIR-domain-containing proteins (tol-1 and tir-1, the latter encoding the SARM orthologue) led to an anticipation of a role for TIR-1 in worm immunity. Couillault et al. showed that inactivation of tir-1 by RNA interference led to decreased worm survival in response to fungal infection, which was related to decreased expression of two antimicrobial peptides. Surprisingly, the activity of TIR-1 was independent of TOL-1. This study also showed that there are five isoforms of TIR-1, all of which contain the two SAM motifs and a TIR domain, but differ in their N-termini. Liberati et al.114 showed that TIR-1 functions upstream of PMK-1 (p38 MAPK family 1), a worm p38 MAPK that is known to be important in innate immunity. It was subsequently shown that TIR-1 also has a role in worm development, specifically in the asymmetrical expression of odorant receptors of olfactory neurons, and that this function also involves the regulation of MAPK activation115. Liberati et al. also showed that human SARM, in contrast to the other four mammalian TIR-domaincontaining adaptors, did not induce NF-κB activation when overexpressed114. So, the role of SARM remained a mystery. Recently, however, SARM has been assigned a role in TLR signalling, and, in contrast to the other four adaptors, it is a negative regulator of NF-κB and IRF activation5 . SARM expression was shown to specifically block TRIF-dependent transcription-factor activation and gene induction, without affecting the MyD88-dependent pathway or non-TLR signalling by TNF or RIG-I (FIG. 4). Inhibition of TRIF involved direct interaction between TRIF and SARM. Knockdown of SARM expression in primary human peripheral-blood mononuclear cells led to increased polyI:C- and LPS-induced chemokine and cytokine expression. Treatment of cells with LPS led to a marked increase of SARM protein levels, thereby indicating a mechanism for specific negative feedback of the TRIF pathway of TLR4 (and TLR3) signalling. Interestingly, the SAM and TIR domains of SARM were necessary and sufficient for inhibition, and deletion of the N-terminus of SARM increased its expression and rendered the protein resistant to regulation by LPS. Hence, the N-terminus might contain motifs that destabilize SARM, which are then somehow regulated by LPS stimulation. The N-terminus of TIR-1 in C. elegans also seems to have a regulatory role, and, similar to SARM, the SAM motifs and TIR domain of TIR-1 are essential for function115. It is unclear how SARM inhibits TRIF function: it could be that the interaction between the two adaptors prevents the recruitment of downstream effector proteins by TRIF (such as RIP1, TRAF6 and TBK1), or alternatively SARM might recruit an as-yet-unknown TRIF inhibitor through its SAM motifs. It will be important to clarify the mechanism of SARM inhibition of TRIF, the rationale for why SARM selectively targets TRIF and whether SARM has further functions in TLR signalling.